This post accompanies a lightning talk given at DevNet Create 2021 where I had 10 minutes to convince network engineers that they might like to learn Go in addition to Python, the lingua franca of network engineers. To be clear, I’m not suggesting you should necessarily learn it instead, but learn it alongside – who knows though, you might just love it!

First of all, I should just cover the title of the talk: “Come Go With Me”. Essentially I looked for any song with Go in it’s title (and trust me, there are plenty), but after seeing Mavis Staples on Jools Holland’s Hootenanny from 2017 I went with The Staple Singers, which has the full title “If You’re Ready (Come Go With Me)”.

In addition, this talk came about whilst I was part way through a good book, so many of the quotes are courtesy of that book: “Cloud Native Go” by Matthew A. Titmus.

With that out of the way, I’ll get on with it.

The talk was in the DevNet Create topic of “Interoperability & Quality” with an abstract as follows:

An overview of why network engineers should learn the Go programming language and why it can improve the quality, performance and portability of their applications.

So we’ll try and pick on some of these points as we go through.

What Is Go?

So just in case you haven’t come across Go before, from an article titled The 10 Most Popular Programming Languages to Learn in 2021, they say:

Also referred to as Golang, Go was developed by Google to be an efficient, readable, and secure language for system-level programming. It works well for distributed systems… While it is a relatively new language, Go has a large standards library and extensive documentation

You can find out more about Go on the official website and we’ll talk more about it during this post.

Domain Applicability

One of the first things we need to think about when choosing a new language is domain applicability. If you’ve ever attended any DevNet Express training, this will be one of the big reasons they give as to why Python is so popular with network engineers – because there are so many tools and existing code that can be used to perform your day job that it doesn’t make sense to use anything else.

Well, I guess I’m here to tell you that Go is the new kid on the block and that, whilst already popular in other areas, it is gradually getting a lot more focus from the network community.

For example, one popular Python automation framework is Nornir. The same people that created Nornir have created Gornir, a pluggable framework with inventory management to help operate collections of devices. It’s similar to nornir but in golang.

Another example is the scrapli library, a python library focused on connecting to devices, specifically network devices (routers/switches/firewalls/etc.) via Telnet or SSH. This again appears to be in the early stages of being replicated in Go as scrapligo, a Go library focused on connecting to devices, specifically network devices (routers/switches/firewalls/etc.) via SSH and NETCONF.

In addition, when we start talking about Infrastructure as Code, Ansible is a hugely popular framework. It allows you to modify configuration over time. The problem with this though is that after a while it can be difficult to know what “state” your environment is in, known as “configuration drift”. Anyone who has built a linux server and added packages, updgrades and patches to it over time will know what I mean – could you build an identical server? The term for this is apparently a Snowflake Server.

The same thing is happening with network configuration and automation. We can add “continuous delivery” to the mix to try and resolve some of the issues, but for me, this procedural approach doesn’t lend itself to large infrastructure deployments and hybrid environments.

You may well have found yourself in the same position, getting to the point where Ansible is a useful tool, but a complimentary component is required in order to maintain “desired state configuration”. This is a term I’ve borrowed from Microsoft and is a Powershell component for managing servers using declaritive scripting and I think it’s a term which accurately describes what we mean – we say what we want our environment to look like, and that’s what gets created. You never make changes to individual components, you just redeploy them from the new state.

For this, we have Terraform by Hashicorp. I suspect this isn’t the first time you’ve heard of it, but essentially it enables us to describe our environment in declaritive configuration files, allows us to check what changes are going to be deployed and then applies them when we’re ready. No configuration drift here!

Terraform has the concept of providers which are essentially connectors to the various components of your infrastructure, and with Cisco teaming up with Hashicorp earlier this year, we’re only going to see more and more providers being created for Cisco technology, and Terraform becoming an increasingly important part of your networking tool bag.

So, where am I going with this, well, guess what Terraform is written in? And guess what the providers are written in – you guessed it… Go! If you want to keep up with the direction infrastructure as code is going, it might be prudent to at least take a look at Go. That way, you’ll be able to contribute and maybe create providers of your own.

In addition to Terraform, there are many other “cloud native” components written in Go:

We have Docker to build containers, and Kubernetes to orchestrate them. Prometheus lets us monitor them. Consul lets us discover them. Jaeger lets us trace the relationships between them. These are just a few examples, but there are many, many more, all representative of a new generation of technologies: all of them are “cloud native,” and all of them are written in Go.

So the Go networking community is definitely growing and I think you can see that reflected in the Go code available on DevNet Code Exchange.

Now we’ll take a look at a couple of areas relating to the language itself which I think are relevant to the networking community.

Simplicity

Go is a compiled language like C or Java rather than a dynamic/interpreted language like Python or JavaScript, which typically puts people off because they think it will be difficult to learn and slow to work with.

In terms of being difficult to learn, Go encourages simplicity and productivity over clutter and complexity. From “Cloud Native Go”:

Go was designed with large projects with lots of contributors in mind. Its minimalist design (just 25 keywords and 1 loop type), and the strong opinions of its compiler, strongly favor clarity over cleverness. This in turn encourages simplicity and productivity over clutter and complexity. The resulting code is relatively easy to ingest, review, and maintain, and harbors far fewer “gotchas.”

Seriously, 1 loop type – life changing 😉

In addition, Go is a “Garbage Collected” language in the same way that Java and C# are. Some would say this is a disadvantage from a performance perspective (which we’ll come to), but from a simplicity point of view, this definitely helps because it means that you don’t need to worry directly about memory management like with languages such as C and Rust. This makes it much easier to transition from, or learn alongside, Python.

Performance

I mentioned before that people may be put off because they think compiled languages may be slow to work with. This is usually because of the compilation step. In this section, I’m going to mention a few performance advantages that Go has over other compiled languages and also over interpreted languages.

Compilation

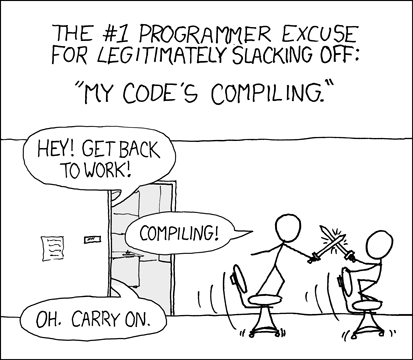

A question that might be important for those coming from Python is the time it takes to compile their code in a compiled language. This is often an argument given in favour of dynamic languages. However, the fast compilation that you get with Go makes it feel like a dynamic language but with all the benefits of a compiled language – it’s no coincidence that dynamic languages are adding types.

The story goes that Google engineers designed Go whilst waiting for their other programs to compile, and compilation time was, and still is, a major design consideration. From the Go FAQ relating to why they created another language:

One had to choose either efficient compilation, efficient execution, or ease of programming; all three were not available in the same mainstream language. Programmers who could were choosing ease over safety and efficiency by moving to dynamically typed languages such as Python and JavaScript rather than C++ or, to a lesser extent, Java.

Where they then go on to say (emphasis mine):

Go addressed these issues by attempting to combine the ease of programming of an interpreted, dynamically typed language with the efficiency and safety of a statically typed, compiled language. It also aimed to be modern, with support for networked and multicore computing. Finally, working with Go is intended to be fast: it should take at most a few seconds to build a large executable on a single computer.

By way of an example (from Cloud Native Go):

building all 1.8 million lines of Go in Kubernetes v1.20.2 on a MacBook Pro with a 2.4 GHz 8-Core Intel i9 processor and 32 GB of RAM required about 45 seconds of real time

So compiling and running your average “script” (or even larger ones) shouldn’t be a problem!

Code Execution

For me, performance isn’t just about how fast the code runs – if that’s your main requirement, then other languages might be a a better fit (looking at you Rust). I suspect though, that unless you’re writing code for embedded systems, or creating your own operating system, it won’t be that big of a deal, since Go compares favourably to other compiled languages, even those with manual memory management, and is far easier to learn too.

Being a compiled language, Go will obviously be faster than any interpreted language. By way of an example, benchmarks show Python to be 10 to 100 times slower than compiled languages. Check out the benchmarks game for a comparison.

Containerisation

Finally it might seem odd to add containerisation into performance, but if you’re building containers, either locally or part of your CI/CD pipeline and pushing/pulling containers around everywhere, the size of those containers is going to be pretty important.

By way of a simple test I created some standard containers for a simple Hello World application and compared their sizes. Firstly I created the images using the standard containers golang:latest and python:3.7 for Go and Python respectively. As you can see, they are fairly well matched.

| Repository | Size |

|---|---|

| big-python | 915MB |

| big-go | 942MB |

However, if we apply a little more thought and use more appropriate containers for production, we can make these images much smaller. In this case, I used scratch and python:3.7-alpine for Go and Python respectively.

| Repository | Size |

|---|---|

| small-python | 41.9MB |

| small-go | 1.2MB |

As you can see there is still a reasonable difference in the container size and this is due to the fact that Go binaries are compiled with all their requirements and don’t require a runtime environment to execute. Not only does this improve the performance and portability of your application, but will also no doubt have an impact on the security of it too.

You could argue that the python image could be made smaller, but this would most likely be at the expense of simplicity and readability, and that’s never a good thing.

Clearly there are a lot of other areas around performance we could take on, but I’m going to move onto the final piece which I just mentioned, and that’s portability.

Portability

The final thing I wanted to talk about briefly is portability, mainly because I have found this to be really useful.

Essentially Go provides the ability to easily share a whole application with any user without requiring them to have any particular environment set up.

This is because when you compile your Go code it produces a statically linked executable binary. This just means that it wraps in any dependencies and the runtime into a single executable file. So when you share it with someone, they don’t need the Go compiler installed on their machine, or any of the libraries that you used to create the application.

Contrast this with a dynamic language like Python or Javascript where you need to ensure that the recipient has the Python or Javascript interpreter on their machine. Most often this will involve ensuring they have the correct version installed too. And finally, on receipt of your application, they will have to install any required libraries that you used to create it.

The ability to create easy to use applications that are easily shared with colleagues without requiring anything of them, from experience, is a breath of fresh air!

I hope this post has been useful. If you have any comments or feedback, please feel free to reach out to me on twitter.

Resources

- DevNet Code Exchange where there are libraries for many Cisco platforms, including:

- ACI client for Go;

- Terraform provider for ACI;that uses the aforementioned ACI client for Go;

- SDWAN client for Go;

- Terraform provider for SDWAN

- Meraki CLI Utility using the Go Dashboard API, both by Dexter Park;

- Gornir - Go implementaton of nornir by the same people!

- Gomiko - Go implementation of netmiko by Ali-aqrabawi;

- scrapligo - Go library focused on connecting to devices, specifically network devices (routers/switches/firewalls/etc.) via SSH and NETCONF;

- Protobuf Files for Cisco networking operating systems;

- Webex Library by Jose Bogarín